When Art Meets Medicine: A Conversation on Anatomy, Surgery, and the Human Form

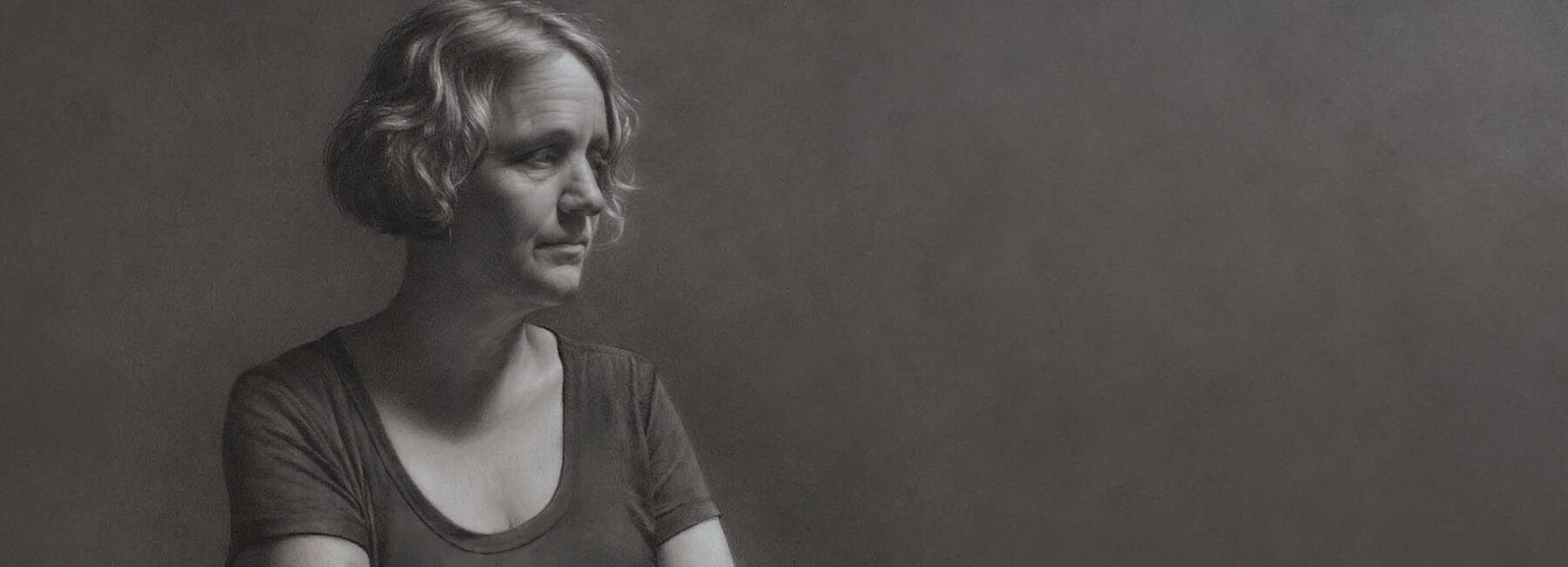

On a November evening at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago, two distinct yet surprisingly parallel worlds converged. Dr. David Morris, a plastic surgeon specializing in pediatric reconstruction, and artist Mindy Whitmore, co-founder and instructor at Vitruvian Studio, whose work focuses on anatomical écorché, came together to explore a question that has fascinated both disciplines for centuries: How can we better understand the human form?

Their conversation, part of the museum’s yearlong “Artistry of Plastic Surgery” exhibition, focus on the idea that, from a certain point of view, surgeons and artists are engaged in the same fundamental pursuit. Both seek to understand the form and structure of the human body to better represent, reshape and reimagine it for their own purposes.

The Common Ground of Physicians and Artists

Dr. Morris embodies this intersection personally. By day, he performs delicate reconstructive procedures on children and young adults. By night, he works in his studio, creating figurative drawings and paintings that reflect his deep understanding of anatomy. As he explains in the talk, his path through both disciplines has been shaped by the same foundational skill: the ability to truly see and understand human anatomy.

Mindy Whitmore brings a complementary perspective. As an artist who sculpts anatomical models for medical education, and teaches anatomy to both art students and medical students, she bridges these worlds daily. Her work in anatomical écorché—figures that reveal the skeletomuscular structures without skin—continues a tradition stretching back to the Renaissance, when artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo studied cadavers to perfect their understanding of the human form.

A Historical Journey Through Art and Medicine

The talk takes viewers on a fascinating historical journey, beginning in the late Renaissance when the study of anatomy brought profound changes to both art and medicine. Dr. Morris traces the evolution of anatomical illustration, from early woodcuts to the detailed engravings of Andreas Vesalius, showing how artists and physicians collaborated to document and understand the body’s intricate architecture.

This historical partnership took on urgent new dimensions during the World Wars, when the devastating facial injuries suffered by soldiers forced surgeons to become innovators and artists in their own right. As the museum’s exhibition explores, these wartime surgeons drew upon artistic principles of proportion, symmetry, and form to reconstruct shattered faces—pioneering techniques that would eventually evolve into modern plastic surgery.

Learning to See: The Discipline of Drawing

One of the talk’s most compelling themes is the discipline required to truly master anatomical understanding. Both speakers emphasize that whether you’re training to be a surgeon or an artist, the path is the same: thousands of hours of careful observation, repetition, and practice.

Whitmore shares insights into her teaching philosophy, explaining how learning anatomy is like learning a language or a musical instrument, Just as you have to play scales before you can play Chopin, artists can expect to produce countless “bad drawings” before achieving mastery. She references John Singer Sargent’s seemingly effortless brushwork, revealing the hours of repetition and scraped-away attempts that preceded each perfect stroke.

Dr. Morris adds the importance of finding the right mentor—someone who can see your blind spots and guide your development. Both speakers acknowledge that in our age of social media and instant results, it’s easy to forget that mastery takes time, patience, and lots of unglamorous work.

The Living Body vs. The Cadaver

In the Q&A session, an intriguing question emerges about whether écorché sculptures and modern 3D scanning could replace cadaver dissection for learning anatomy. The speakers offer a nuanced response: while technology and models have their place, they note some important distinctions in how anatomical study has evolved.

Dr. Morris points out an interesting historical detail: Vesalius used a pulley system to suspend cadavers vertically during dissection, allowing him to rotate and position the body as needed for his work. In contrast, modern medical students typically dissect cadavers positioned horizontally on tables. Dr. Morris observes that this difference in positioning—combined with the effects of preservation and gravity—means the forms that medical students encounter can look quite different from the muscular arrangements visible in classical anatomical illustrations.

Whitmore emphasizes that while cadaver study offers valuable insights into anatomical relationships, the fixed, lifeless quality of preserved tissue lacks the aesthetic qualities that artists seek to understand. The living, moving body remains the ultimate teacher for those studying form and proportion.

An Invitation to Explore

This conversation offers a rare glimpse into the shared language of art and medicine. Whether you’re an artist seeking to deepen your anatomical knowledge, a medical professional interested in the artistic dimensions of your work, or simply someone fascinated by the human form, this talk provides valuable insights into how we see, study, and ultimately attempt to capture the remarkable architecture of the human body.

Watch the full video to experience the complete conversation, view examples of both speakers’ work, and hear their detailed discussion of anatomical study from Renaissance masters to contemporary practice. You’ll come away with a deeper appreciation for the centuries-old dialogue between art and medicine—and perhaps a new way of seeing the bodies we all inhabit.

Responses